|

The Nuclear Death of a Nuclear Scientist By Barrie Zwicker

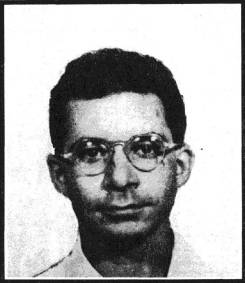

"PERHAPS IT IS MERCIFUL that minds can be immunized against dread. But in the circumstances it is also dangerous. And so it seems well, from time to time, to recall such events as may serve to keep comprehension fresh and exquisite. Among these events may be counted the last days of Dr. Louis A. Slotin, physicist and biochemist who was born in Winnipeg in 1910 and who died in the secret atomic city of Los Alamos at the age of 35." These are the words of writer Barbara Moon, from an article which appeared in the October 1961 issue of Maclean's and won the President's Medal as the top magazine piece in Canada that year.  Dr. Louis A. Slotin The article is at least as significant and timely today as it was then. Because there remains ignorance of, or denial of, the intimate effects on the human body of the burst of radiation emitted in the eighth nanosecond of a nuclear bomb detonation, we reprint edited excerpts from "The Nuclear Death of a Nuclear Scientist." * * * * HE WAS A STUDIOUS, self-possessed, bespectacled little boy. At The University of Manitoba he grew into a brilliant student of chemistry, with a particular knack for designing the swift, imaginative experiment that would test a theory, and for improvising the necessary apparatus. He also grew into a seemly youth, reserved and quiet but with a quizzical air that lent him poise, and also what a friend later called "a romantic and elaborate view of himself and the world." He earned his doctorate at The University of London and at the same time turned himself into a crack bantamweight boxer. * * * By the age of 30, in the laboratory with his colleagues, he was a leader. At lunch with them he would neglect his food while he talked, reaching among the flatware with his finely shaped, expressive hands, smoothing out a paper napkin, covering it with diagrams . . . * * * In 1944 he was recruited to Los Alamos . . . After a time there he became, in effect, chief armorer of the United States. * * *

In the glove compartment of his cream Dodge convertible Slotin kept something that looked like a hydroelectric bill. It was the receipt made out by the U.S. Army when it took delivery from him of the epochal A-bomb core, the first one, tested at Alamogordo. For Slotin's job, along with some others, was to run final tests on the active core of each precious A-bomb to make sure it would produce the explicit nuclear burst it was supposed to. * * * TUESDAY, May 21, 1946 * * * It was around 3 o'clock . . . in a bare, white-painted room, unfurnished except for the sparse, unimposing equipment of critical assembly tests. They watched as Slotin set up the experiment on the centre table. * * * The assembly was a nickel-plated core of plutonium, weighing about 13 pounds, in the form of two hemispheres which, when put together, rather resembled a gray metallic curling stone. They were the active guts of one of the three A-bombs due to be shipped to Bikini for Operation Crossroads. The plutonium rested in a half-shell of beryllium, a metal that can bounce escaping neutrons back into the mass of an active metal so they are conserved for the fission process . . . (and) there was a matching upper half-shell of beryllium. The technique of this experiment consisted of lowering this upper shell until it almost met the lower shell . . . A slow, controlled chain reaction would start. But . . . if the two half-shells came to within an eighth of an inch of each other — thus making a critical surplus of neutrons available simultaneously — a fast, uncontrolled reaction called a "prompt burst" would ensue. * * * . . . this time the assembly didn't perform according to Hoyle. So Slotin improvised. What Slotin did was to remove two tiny safety devices — spacers — that served to block the upper beryllium hemisphere from closing absolutely on the lower one. Instead he lowered one side (of the upper shell) onto the blade of a screwdriver . . . * * * At exactly 3:20 Graves heard a click as the screwdriver blade escaped the crack and the beryllium shell came down on the rest of the assembly. In the same moment a blue glow surrounded the assembly; those in the room felt a quick flux of heat. That was all. * * * . . . Slotin . . . (dropped) the beryllium shell onto the floor. It was still 3:20 and he had just been killed. * * * Slotin had vomited once, in the ambulance on the way to the Los Alamos hospital. By 6:30 p.m. his left hand was fat and reddened. * * * That night Morrison, who had seen the aftermath of Hiroshima, consulted workmen in the special machine shop attached to the lab and together they began to invent a contrivance with a book-rack to stretch across a hospital bed, strings to clip to every page of a book, a ratchet system to turn the pages and a switch to invoke the ratchet. The switch was placed so it could be operated by the reader's elbow. It was a reading-machine — for someone who was not going to have hands to use. * * * WEDNESDAY, May 22 * * * FRIDAY, May 24 * * * SATURDAY, May 25 * * * SUNDAY, May 26 * * * MONDAY, May 27 Slotin passed quickly into a toxic state; his temperature and pulse rate rose rapidly; his abdomen became stiff and distended; his gastrointestinal system broke down completely; all his skin turned to a deep angry puce. His body was dissolving into protoplasmic debris. * * * TUESDAY, May 28 * * * WEDNESDAY, May 29 * * * THURSDAY, May 30

Pubslished in SOURCES Summer 83

Sources |