| Home | Sources Directory | News Releases | Calendar | Articles | | Contact | |

Destruction under the Mongol Empire

Destruction under the Mongol Empire refers to widespread loss of life and devastation caused by the Mongolian conquests of the 13th century.

Mongol raids and invasions were generally regarded as some of the deadliest in human history. Nonetheless due consideration should be given to the age of sources recounting the events, and that the accounts were written primarily by survivors of the Mongol attacks.

Contents |

[edit] Background

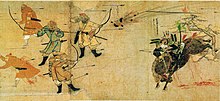

The Mongol style of warfare was an outgrowth of their nomadic way of life, coupled with experience gained in fighting tribes such as the Naimans, Keraits, and Uyghurs. Their strategies were swift and short attacks to plunder each other and disappear quickly.

There was long-standing enmity between Mongolian tribes and China because Mongolian nomads constantly pillaged Chinese cities and settlements because of its greater wealth. Times on the Central Asian steppes were sometimes complicated by seasonal cold temperatures such as zud that resulted in large number of livestock being lost during the winter, which made subsistence difficult. The nomads also didn't practice farming in the traditional sense. The Chinese sought to defuse the Mongol threat by fomenting inter-tribal strife amongst the various Mongol factions who were known to habitually feud amongst themselves due to numerous reasons such as plunder, misunderstanding and vendetta. Because the Gobi lies traditionally between Mongolian region and China, the Chinese couldn't punish and drive away the Mongols all the way. Even if they closed ranks on the Mongol settlements, Mongols would pack up their yurts and move quickly. The Mongols viewed China as rich; the Chinese viewed Mongols as poor and uncivilized "barbarians." The Mongols referred to the Jin Dynasty of northern China, invaded under Genghis Khan, as "Altan Ulus" or "Golden Nation" (this is not necessarily a reference to wealth, as the Chinese character for "Jin" in "Jin Dynasty" also means "metal" or "gold"), while the Goryeo Dynasty called the Mongols the "most inhuman of northern barbarians".[1]

[edit] Strategy

Genghis Khan, his generals and successors preferred to offer their enemies the chance to surrender without resistance in order to avoid war, to become vassals by sending tribute, accepting Mongol residents, and/or contributing troops. The Khans guaranteed protection only if the populace submitted to Mongol rule and was obedient to it.

Sources record massive destruction, terror and death if there was resistance. David Nicole notes in The Mongol Warlords: "terror and mass extermination of anyone opposing them was a well-tested Mongol tactic." The alternative to submission was total war: if refused, Mongol leaders ordered the collective slaughter of populations and destruction of property. Such was the fate of resisting communities during the invasions of the Khwarezmid Empire, Kievan Rus', Baghdad, China, Armenia, Georgia, Poland, Hungary, and northern Iran.

[edit] Terror

The success of Mongol tactics hinged on fear: to induce capitulation amongst enemy populations. Although perceived as being bloodthirsty, the Mongol strategy of "surrender or die" recognized that conquest by capitulation was more desirable than being forced to continually expend soldiers, food, and money to fight every army and sack every town and city along the campaign's route.

The Mongols frequently faced states with armies and resources much greater than their own - and simply invading everyone was out of the question. Furthermore, a supine nation was more desirable than a sacked one. While both provided the same territorial gains, the former would continue to provide taxes and conscripts long after the conflict ended, whereas the latter would be depopulated and economically worthless once available goods and slaves were seized.

Thus whenever possible, by using the promise of wholesale slaughter as well as the deed, Mongol forces made efficient conquests, in turn allowing them to attack multiple targets and redirect soldiers and matériel where most needed.

The linchpin of Mongol success was the widespread perception amongst their enemies, that they were facing an insurmountable juggernaut that could only be placated by surrender. The Mongols counted on reports of horrifying massacres and torture to terrify their foes. The goal was to convince all-and-sundry that the costs of surrendering were not nearly onerous enough to risk an un-winnable war, given the guarantee of complete annihilation if they lost. This strategy was partially adopted because of the Mongols lesser numbers that if their opponents are not sufficiently subdued, there was a greater chance they can rise again and attack the Mongols when the Mongols left to deal with another town and settlements. This way they were technically covering their rear and flanks and creating the condition where they won't have to fight a people they fought and thought they subdued before and therefore saving resources, in their point of view, on unnecessary second engagement.

As Mongol conquest spread, this form of psychological warfare proved effective at suppressing resistance to Mongol rule. There were tales of lone Mongol soldiers riding into surrendered villages and executing peasants at random as a test of loyalty. Also, it was widely known that a single act of resistance would bring the entire Mongol army down on a town to obliterate its occupants. Thus they are ensuring obedience through fear.[2]

[edit] Demographic changes in war-torn areas

The majority of kingdoms resisting Mongol conquest were taken by force (some were subjected to vassaldom and not complete conquest), their populations mostly massacred; only skilled engineers and artisans were spared, to become slaves. Documents written during or just after Genghis Khan's reign state that following a conquest Mongol soldiers looted, pillaged and raped, while the Khan had first pick of women captives beautiful enough to be spared.

These techniques were used to spread terror and warning to others. Some troops who submitted were incorporated into the Mongol system in order to expand their manpower; this also allowed the Mongols to absorb new technology, knowledge and skills for use in military campaigns against other opponents.

Genghis Khan was by and large tolerant of multiple religions and there are no cases of him or other Mongols engaging in religious war, as long as populations were obedient. He also passed a decree exempting all followers of the Taoist religion from paying taxes. However, all of the campaigns caused deliberate destruction of places of worship, if their populations resisted.[3]

Ancient sources described Genghis Khan's conquests as wholesale destruction on an unprecedented scale in certain geographical regions, causing great demographic changes in Asia. Over much of Central Asia, speakers of Iranian languages were replaced by speakers of Turkic languages: according to the works of the Iranian historian Rashid al-Din, the Mongols killed more than 700,000 people in Merv and more than a million in Nishapur. The total population of Persia may have dropped from 2,500,000 to 250,000 as a result of mass extermination and famine.[4]

China reportedly suffered a drastic decline in population during the 13th and 14th centuries. Before the Mongol invasion, Chinese dynasties reportedly had approximately 120 million inhabitants; after the conquest was completed in 1279, the 1300 census reported roughly 60 million people. While it is tempting to attribute this major decline solely to Mongol ferocity, scholars today have mixed sentiments regarding this subject. Scholars such as Frederick W. Mote argue that the wide drop in numbers reflects an administrative failure to record rather than a de facto decrease whilst others such as Timothy Brook argue that the Mongols created a system of enserfment among a huge portion of the Chinese populace causing many to disappear from the census altogether. Other historians like William McNeill and David Morgan argue that the Bubonic Plague was the main factor behind the demographic decline during this period.

About half the population of Russia may have died during the Mongol invasion of Rus.[5] Colin McEvedy (Atlas of World Population History, 1978) estimates the population of European Russia dropped from 7.5 million prior to the invasion to 7 million afterwards.[6]

Historians estimate that up to half of Hungary's population of two million were victims of the Mongol invasion of Europe.[7]

These population estimates are controversial as lower birth rates, disease, and famine may have had a greater effect on the populations than actual warfare.

[edit] Destruction of culture and property

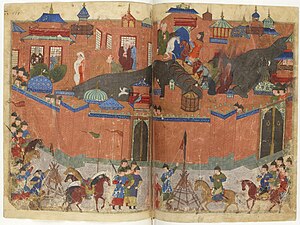

Mongol campaigns in Northern China, Central Asia, Eastern Europe and the Middle East caused extensive destruction, though there are no exact figures available at this time. The cities of Herat, Kiev, Baghdad, Nishapur, Vladimir and Samarkand suffered serious devastation by the Mongol armies.[8][9] For example, there is a noticeable lack of Chinese literature from the Jin Dynasty, predating the Mongol conquest, and in the Battle of Baghdad (1258) libraries, books, literature, and hospitals were burned: some of the books were thrown into the river, in quantities sufficient to "turn the Euphrates black with ink for several days".

The Mongols' destruction of the irrigation systems of Iran and Iraq turned back centuries of effort to improving agriculture and water supply in these regions. The loss of available food as a result may have led to the death of more people from starvation in this area than actual battle did. The Islamic civilization of the Gulf region was not to recover until after the Middle Ages.[10]

[edit] Foods and disease

Mongols were known to burn farmland; when they were trying to take the Ganghwa Island palaces during the invasions (there were at least 6 separate invasions) of Korea under the Goryeo Dynasty, crops were burned to starve the populace. Other tactics included diverting rivers into and from cities and towns, and catapulting diseased corpses over city walls to infect the population. The use of such infected bodies during the siege of Caffa is alleged to have brought the Black Death to Europe by some sources.[11]

[edit] Tribute in lieu of conquest

If a population agreed to pay the Mongols tribute, they were spared invasion and left relatively independent. While resisting populations were usually annihilated and thus did not pay a regular tribute, exceptions to this rule (i.e. countries that resisted and fought the Mongols yet survived and were subsequently allowed to remain autonomous) include Korea (under the Goryeo Dynasty), which finally agreed to pay regular tributes in exchange for vassaldom (and some measure of autonomy as well as the retention of the ruling dynasty), further emphasizing the Mongolian preference for tribute and vassals (which would serve as a somewhat regular and continuous source of income) as opposed to outright conquest and destruction (which brought in a one-time quantity of resources).

Different tributes were taken from different cultures. For instance, Goryeo was assessed at 10,000 otter skins, 20,000 horses, 10,000 bolts of silk, clothing for 1,000,000 soldiers, and a large number of children and artisans as slaves.[12]

[edit] References

- ^ http://medieval2.heavengames.com/m2tw/history/events/mongol_invasions_korea/index.shtml

- ^ Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World - Jack Weatherford

- ^ Man, John. Genghis Khan : Life, Death and Resurrection (London; New York : Bantam Press, 2004) ISBN 0-593-05044-4.

- ^ Battuta's Travels: Part Three - Persia and Iraq

- ^ History of Russia, Early Slavs history, Kievan Rus, Mongol invasion

- ^ Mongol Conquests

- ^ Welcome to Encyclopædia Britannica's Guide to History

- ^ Morgan, David (1986). The Mongols (Peoples of Europe). Blackwell Publishing. pp. 74'75. ISBN 0-631-17563-6.

- ^ Ratchnevsky, Paul (1991). Genghis Khan: His Life and Legacy. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 131'133. ISBN 0-631-16785-4.

- ^ The Story of Civilization: The Age of Faith, by Will and Ariel Durant

- ^ http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/EID/vol8no9/01-0536.htm

- ^ http://www.koreanhistoryproject.org/Ket/C06/E0602.htm

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

SOURCES.COM is an online portal and directory for journalists, news media, researchers and anyone seeking experts, spokespersons, and reliable information resources. Use SOURCES.COM to find experts, media contacts, news releases, background information, scientists, officials, speakers, newsmakers, spokespeople, talk show guests, story ideas, research studies, databases, universities, associations and NGOs, businesses, government spokespeople. Indexing and search applications by Ulli Diemer and Chris DeFreitas.

For information about being included in SOURCES as a expert or spokesperson see the FAQ or use the online membership form. Check here for information about becoming an affiliate. For partnerships, content and applications, and domain name opportunities contact us.