| Home | Sources Directory | News Releases | Calendar | Articles | | Contact | |

Pseudoscience

Pseudoscience is a methodology, belief, or practice that is claimed to be scientific, or that is made to appear to be scientific, but which does not adhere to an appropriate scientific methodology, lacks supporting evidence or plausibility, or otherwise lacks scientific status.[1] The term is inherently pejorative, because it is used to assert that something is being inaccurately or deceptively portrayed as science.[2] Accordingly, those labeled as practicing or advocating pseudoscience normally dispute the characterization.[2]

Pseudoscience has been characterised by the use of vague, exaggerated or untestable claims, over-reliance on confirmation rather than refutation, lack of openness to testing by other experts, and a lack of progress in theory development. There is disagreement among philosophers of science and commentators in the scientific community as to whether there is a reliable way of distinguishing pseudoscience from non-mainstream science.[3][4] Paul DeHart Hurd, who is among the science educators who have taught courses on the topic,[5] wrote that part of gaining scientific literacy is being able to tell science apart from "pseudo-science, such as astrology, quackery, the occult, and superstition".[6]

Contents |

[edit] Etymology

Although the term pseudo-science has been in use since the late 18th century, attested in 1796 in reference to alchemy,[7][8] the concept of pseudoscience as antagonistic to bona fide science appears to have emerged in the mid-19th century. Among the first recorded uses of the word "pseudo-science" in this sense was in 1844 in the Northern Journal of Medicine, I 387: "That opposite kind of innovation which pronounces what has been recognized as a branch of science, to have been a pseudo-science, composed merely of so-called facts, connected together by misapprehensions under the disguise of principles". An earlier recorded use of the term in its present sense was in 1843 by the French physiologist François Magendie.[9]

[edit] Overview

The standards for determining whether a body of knowledge, methodology, or practice is scientific can vary from field to field. There are, however, a number of basic principles that are widely agreed upon by scientists, such as reproducibility and intersubjective verifiability.[11] Such principles aim to ensure that relevant evidence can be measurably reproduced under the same conditions, which allows further investigation to determine whether a hypothesis or theory related to given phenomena is both valid and reliable for use by others, including other scientists and researchers. It is expected that the scientific method will be applied throughout, and that bias will be controlled or eliminated, by double-blind studies, or statistically through fair sampling procedures. All gathered data, including experimental/environmental conditions, are expected to be documented for scrutiny and made available for peer review, thereby allowing further experiments or studies to be conducted to confirm or falsify results, as well as to determine other important factors such as statistical significance, confidence intervals, and margins of error.[12]

In the mid-20th century Karl Popper suggested the criterion of falsifiability to distinguish science from non-science.[13] He gave astrology and psychoanalysis as examples of pseudoscience, and Einstein's theory of relativity as an example of science. Statements such as "God created the universe" may be true or false, but no tests can be devised that could prove them false, so they are not scientific; they lie outside the scope of science. Popper subdivided non-science into philosophical, mathematical, mythological, religious and/or metaphysical formulations on the one hand, and pseudoscientific formulations on the other'though without providing clear criteria for the differences.[14] More recently, Paul Thagard (1978) proposed that pseudoscience is primarily distinguishable from science when it is less progressive than alternative theories over a long period of time, and the failure of proponents to acknowledge or address problems with the theory.[15] Mario Bunge has suggested the categories of "belief fields" and "research fields" to help distinguish between science and pseudoscience.[16]

Philosopher of science Paul Feyerabend has argued, from a sociology of knowledge perspective, that a distinction between science and non-science is neither possible nor desirable.[17][18] Among the issues which can make the distinction difficult are that both the theories and methodologies of science evolve at differing rates in response to new data.[19] In addition, the specific standards applicable to one field of science may not be those employed in other fields. Thagard also writes from a sociological perspective and states that "elucidation of how science differs from pseudoscience is the philosophical side of an attempt to overcome public neglect of genuine science."

[edit] Identifying pseudoscience

A field, practice, or body of knowledge might reasonably be called pseudoscientific when (1) it is presented as consistent with the accepted norms of scientific research; but (2) it demonstrably fails to meet these norms, most importantly, in misuse of scientific method. [20][citation needed]

Karl Popper stated that it is insufficient to distinguish science from pseudoscience, or from metaphysics, because of its adherence to the empirical method, which is essentially inductive, based on observation or experimentation.[21] He proposed a method to distinguish between genuine empirical, non-empirical or even pseudo-empirical methods. The later case was exemplified by astrology which appeals to observation and experimentation. But while it had astonishing empirical evidence based on observation, on horoscopes and biographies it crucially failed to adhere to acceptable scientific standards.[21]

Popper proposed falsifiability as an important criterion in distinguishing science from pseudoscience. To demonstrate this point, Popper[21] gave two cases of human behavior and typical explanations from Freud and Adler's theories: "that of a man who pushes a child into the water with the intention of drowning it; and that of a man who sacrifices his life in an attempt to save the child."[21] From Freud's perspective, the first man would have suffered from psychological repression, probably originating from an Oedipus complex whereas the second had attained sublimation. From Adler's perspective, the first and second man suffered from feelings of inferiority and had to prove himself which drove him to commit the crime or, in the second case, rescue the child. Popper was not able to find any counter-examples of human behavior in which the behavior could not be explained in the terms of Adler's or Freud's theory. Popper argued[21] that it was that the observation always fitted or confirmed the theory which, rather than being its strength, was actually its weakness.

In contrast, Popper[21] gave the example of Einstein's gravitational theory which predicted that "light must be attracted by heavy bodies (such as the sun), precisely as material bodies were attracted."[21] Following from this, stars closer to the sun would appear to have moved a small distance away from the sun, and away from each other. This prediction was particularly striking to Popper because it involved considerable risk. The brightness of the sun prevented this effect from being observed under normal circumstances, so photographs had to be taken during an eclipse and compared to photographs taken at night. Popper states, "If observation shows that the predicted effect is definitely absent, then the theory is simply refuted."[21] Popper summed up his criterion for the scientific status of a theory as depending on its falsifiability, refutability, or testability.

Paul R. Thagard used astrology as a case study to distinguish science from pseudoscience and proposed principles and criteria to delineate them.[22] First, astrology has not progressed in that it has not been updated nor added any explanatory power since Ptolemy. Second, it has ignored outstanding problems such as the precession of equinoxes in astronomy. Third, alternative theories of personality and behavior have grown progressively to encompass explanations of phenomena which astrology statically attributes to heavenly forces. Fourth, astrologers have remained uninterested in furthering the theory to deal with outstanding problems or in critically evaluating the theory in relation to other theories. Thagard intended this criterion to be extended to areas other than astrology. He believed that it would delineate pseudoscientific practices as witchcraft and pyramidology, while leaving physics, chemistry and biology in the realm of science. Biorhythms, which like astrology relied uncritically on birth dates, did not meet the criterion of pseudoscience at the time because there were no alternative explanations for the same observations. The use of this criterion has the consequence that a theory can at one time be scientific and at another pseudoscientific.[22]

Science is also distinguishable from revelation, theology, or spirituality in that it offers insight into the physical world obtained by empirical research and testing.[23] For this reason, the teaching of creation science and intelligent design theory has been strongly condemned in position statements from scientific organisations.[24] The most notable disputes concern the effects of evolution on the development of living organisms, the idea of common descent, the geologic history of the Earth, the formation of the solar system, and the origin of the universe.[25][citation needed] Systems of belief that derive from divine or inspired knowledge are not considered pseudoscience if they do not claim either to be scientific or to overturn well-established science.

Some statements and commonly held beliefs in popular science may not meet the criteria of science. "Pop" science may blur the divide between science and pseudoscience among the general public, and may also involve science fiction.[26] Indeed, pop science is disseminated to, and can also easily emanate from, persons not accountable to scientific methodology and expert peer review.

If the claims of a given field can be experimentally tested and methodological standards are upheld, it is not "pseudoscience", however odd, astonishing, or counter-intuitive. If claims made are inconsistent with existing experimental results or established theory, but the methodology is sound, caution should be used; science consists of testing hypotheses which may turn out to be false. In such a case, the work may be better described as ideas that are not yet generally accepted. Protoscience is a term sometimes used to describe a hypothesis that has not yet been adequately tested by the scientific method, but which is otherwise consistent with existing science or which, where inconsistent, offers reasonable account of the inconsistency. It may also describe the transition from a body of practical knowledge into a scientific field.[27]

An example of characterization as pseudoscience by a national scientific body is provided by the US National Science Foundation (NSF), whose statements are generally recognized to harmonize with the scientific consensus in the United States.[28] In 2006 the NSF issued an executive summary of a paper on science and engineering which briefly discussed the prevalence of pseudoscience in modern times. It said that "belief in pseudoscience is widespread" and, referencing a Gallup Poll,[29] stated that belief in the ten commonly believed examples of paranormal phenomena listed in the poll were "pseudoscientific beliefs". The ten items were: "extrasensory perception (ESP), that houses can be haunted, ghosts, telepathy, clairvoyance, astrology, that people can communicate mentally with someone who has died, witches, reincarnation, and channelling."[28]

The following have been proposed to be indicators of poor scientific reasoning.

[edit] Use of vague, exaggerated or untestable claims

- Assertion of scientific claims that are vague rather than precise, and that lack specific measurements.[30]

- Failure to make use of operational definitions (i.e. publicly accessible definitions of the variables, terms, or objects of interest so that persons other than the definer can independently measure or test them).[31] (See also: Reproducibility)

- Failure to make reasonable use of the principle of parsimony, i.e. failing to seek an explanation that requires the fewest possible additional assumptions when multiple viable explanations are possible (see: Occam's Razor)[32]

- Use of obscurantist language, and use of apparently technical jargon in an effort to give claims the superficial trappings of science.

- Lack of boundary conditions: Most well-supported scientific theories possess well-articulated limitations under which the predicted phenomena do and do not apply.[33]

- Lack of effective controls, such as placebo and double-blind, in experimental design.

[edit] Over-reliance on confirmation rather than refutation

- Assertions that do not allow the logical possibility that they can be shown to be false by observation or physical experiment (see also: falsifiability)[34]

- Assertion of claims that a theory predicts something that it has not been shown to predict.[35] Scientific claims that do not confer any predictive power are considered at best "conjectures", or at worst "pseudoscience" (e.g. Ignoratio elenchi)[36]

- Assertion that claims which have not been proven false must be true, and vice versa (see: Argument from ignorance)[37]

- Over-reliance on testimonial, anecdotal evidence, or personal experience. This evidence may be useful for the context of discovery (i.e. hypothesis generation) but should not be used in the context of justification (e.g. Statistical hypothesis testing).[38]

- Presentation of data that seems to support its claims while suppressing or refusing to consider data that conflict with its claims.[39] This is an example of selection bias, a distortion of evidence or data that arises from the way that the data are collected. It is sometimes referred to as the selection effect.

- Reversed burden of proof. In science, the burden of proof rests on those making a claim, not on the critic. "Pseudoscientific" arguments may neglect this principle and demand that skeptics demonstrate beyond a reasonable doubt that a claim (e.g. an assertion regarding the efficacy of a novel therapeutic technique) is false. It is essentially impossible to prove a universal negative, so this tactic incorrectly places the burden of proof on the skeptic rather than the claimant.[40]

- Appeals to holism as opposed to reductionism: Proponents of pseudoscientific claims, especially in organic medicine, alternative medicine, naturopathy and mental health, often resort to the "mantra of holism" to explain negative findings.[41]

[edit] Lack of openness to testing by other experts

- Evasion of peer review before publicizing results (called "science by press conference").[42] Some proponents of theories that contradict accepted scientific theories avoid subjecting their ideas to peer review, sometimes on the grounds that peer review is biased towards established paradigms, and sometimes on the grounds that assertions cannot be evaluated adequately using standard scientific methods. By remaining insulated from the peer review process, these proponents forgo the opportunity of corrective feedback from informed colleagues.[43]

- Some agencies, institutions, and publications that fund scientific research require authors to share data so that others can evaluate a paper independently. Failure to provide adequate information for other researchers to reproduce the claims contributes to a lack of openness.[44]

- Appealing to the need for secrecy or proprietary knowledge when an independent review of data or methodology is requested.[44]

[edit] Absence of progress

- Failure to progress towards additional evidence of its claims.[45] Terence Hines has identified astrology as a subject that has changed very little in the past two millennia.[46] (see also: Scientific progress)

- Lack of self correction: scientific research programmes make mistakes, but they tend to eliminate these errors over time.[47] By contrast, theories may be accused of being pseudoscientific because they have remained unaltered despite contradictory evidence. The work Scientists Confront Velikovsky (1976) Cornell University, also delves into these features in some detail, as does the work of Thomas Kuhn, e.g. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962) which also discusses some of the items on the list of characteristics of pseudoscience.

- Statistical significance of supporting experimental results does not improve over time and are usually close to the cutoff for statistical significance. Normally, experimental techniques improve or the experiments are repeated and this gives ever stronger evidence. If statistical significance does not improve, this typically shows that the experiments have just been repeated until a success occurs due to chance variations.

[edit] Personalization of issues

- Tight social groups and authoritarian personality, suppression of dissent, and groupthink can enhance the adoption of beliefs that have no rational basis. In attempting to confirm their beliefs, the group tends to identify their critics as enemies.[48]

- Assertion of claims of a conspiracy on the part of the scientific community to suppress the results.[49]

- Attacking the motives or character of anyone who questions the claims (see Ad hominem fallacy).[50]

[edit] Use of misleading language

- Creating scientific-sounding terms in order to add weight to claims and persuade non-experts to believe statements that may be false or meaningless. For example, a long-standing hoax refers to water by the rarely-used formal name "dihydrogen monoxide" (DHMO) and describes it as the main constituent in most poisonous solutions to show how easily the general public can be misled.

- Using established terms in idiosyncratic ways, thereby demonstrating unfamiliarity with mainstream work in the discipline.

[edit] Demographics

| The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. Please improve this article and discuss the issue on the talk page. |

The National Science Foundation stated that, in the USA, "pseudoscientific" beliefs became more widespread during the 1990s, peaked near 2001 and have declined slightly since; nevertheless, pseudoscientific beliefs remain common in the USA.[51] As a result, according to the NSF report, there is a lack of knowledge of pseudoscientific issues in society and pseudoscientific practices are commonly followed. Bunge states that "A survey on public knowledge of science in the United States showed that in 1988 50% of American adults [rejected] evolution, and 88% [believed] astrology is a science"[citation needed]. Other surveys indicate that about a third of all adult Americans consider astrology to be scientific.[52][53][54]

Commentators on pseudoscience perceive it in many fields; for example, pseudomathematics is a term used for mathematics-like activity undertaken by either non-mathematicians or mathematicians themselves which does not conform to the rigorous standards usually applied to mathematical theorems.[citation needed]

[edit] Clinical psychology

Neurologists, clinical psychologists and other academics are concerned,[55] about the increasing amount of what they consider pseudoscience promoted in psychotherapy and popular psychology, and also about what they see as pseudoscientific therapies such as neuro-linguistic programming, EMDR[56] rebirthing, reparenting, Scientology, and Primal Therapy being adopted by government and professional bodies and by the public.[56] They state that scientifically unsupported therapies used by popular or folk psychology might harm vulnerable members of the public, undermine legitimate therapies, and tend to spread misconceptions about the nature of the mind and brain to society at large. Norcross et al..[57] have approached the science/pseudoscience issue by conducting a survey of experts that seeks to specify which theory or therapy is considered to be definitely discredited, and they outline 14 fields that have been definitely discredited.

[edit] Psychological explanations

Pseudoscientific thinking has been explained in terms of psychology and social psychology. The human proclivity for seeking confirmation rather than refutation (confirmation bias),[58] the tendency to hold comforting beliefs, and the tendency to overgeneralize have been proposed as reasons for the common adherence to pseudoscientific thinking. According to Beyerstein (1991), humans are prone to associations based on resemblances only, and often prone to misattribution in cause-effect thinking.

Lindeman argues that social motives (i.e., "to comprehend self and the world, to have a sense of control over outcomes, to belong, to find the world benevolent and to maintain one's self-esteem") are often "more easily" fulfilled by pseudoscience than by scientific information.[59] Furthermore, pseudoscientific explanations are generally not analyzed rationally, but instead experientially. Operating within a different set of rules compared to rational thinking, experiential thinking regards an explanation as valid if the explanation is "personally functional, satisfying and sufficient", offering a description of the world that may be more personal than can be provided by science and reducing the amount of potential work involved in understanding complex events and outcomes.[59]

[edit] Boundaries between science and pseudoscience

The boundary lines between the science and pseudoscience are disputed and difficult to determine analytically, even after more than a century of dialogue among philosophers of science and scientists in varied fields, and despite some basic agreements on the fundaments of scientific methodology.[20][60] The concept of pseudoscience rests on an understanding that scientific methodology has been misrepresented or misapplied with respect to a given theory, but many philosophers of science maintain that different kinds of methods are held as appropriate across different fields and different eras of human history. Paul Feyerabend, for example, disputes whether any meaningful boundaries can be drawn between pseudoscience, "real" science, and what he calls "protoscience", especially where there is a significant cultural or historical distance.

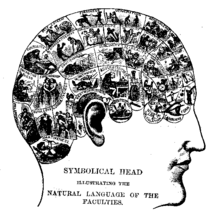

There are well-known cases of fields that were originally considered pseudoscientific but which are now accepted scientific effects or valid hypotheses, for example, continental drift,[61] cosmology,[62] ball lightning,[63] and radiation hormesis.[64][65][66][67] As another example, osteopathy has, according to Kimball Atwood, "for the most part, repudiated its pseudoscientific beginnings and joined the world of rational healthcare" for lower back pain although it is not particularly effective.[68] Others, such as phrenology[citation needed] or alchemy were originally considered scientific, but now are taken as pseudoscience. Further, there are protosciences such as cultural, traditional, or ancient practices such as acupuncture practice and traditional Chinese medicine which do not conform to modern scientific principles, but which are not pseudoscience because their proponents do not claim the practices to be scientific according to today's standards of scientific method.

Larry Laudan has suggested that pseudoscience has no scientific meaning and is mostly used to describe our emotions: "If we would stand up and be counted on the side of reason, we ought to drop terms like 'pseudo-science' and 'unscientific' from our vocabulary; they are just hollow phrases which do only emotive work for us".[69] Likewise, Richard McNally states that "The term 'pseudoscience' has become little more than an inflammatory buzzword for quickly dismissing one's opponents in media sound-bites" and that "When therapeutic entrepreneurs make claims on behalf of their interventions, we should not waste our time trying to determine whether their interventions qualify as pseudoscientific. Rather, we should ask them: How do you know that your intervention works? What is your evidence?"[70]

The term pseudoscience can also have political implications that eclipse any scientific issues. Imre Lakatos, for instance, points out that the Communist Party of the Soviet Union at one point declared that Mendelian genetics was pseudoscientific and had its advocates, including well-established scientists such as Nikolai Vavilov, sent to Gulag,[71] and that the "liberal Establishment of the West" denies freedom of speech to topics it regards as pseudoscience, particularly where they run up against social mores.[72]

[edit] See also

- Analytic philosophy

- Antiscience

- Credulity

- List of topics characterized as pseudoscience

- Neurolinguistic programming

- Pathological science

- Scientism

[edit] Further reading

- Bauer Henry H (2000). Science or Pseudoscience: Magnetic Healing, Psychic Phenomena, and Other Heterodoxies. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0252026010.

- Charpak Georges (2004). Debunked. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801878675.

- Derksen AA (1993). "The seven sins of pseudo-science". J Gen Phil Sci 24: 17'42. doi:10.1007/BF00769513.

- Derksen AA (2001). "The seven strategies of the sophisticated pseudo-scientist: a look into Freud's rhetorical toolbox". J Gen Phil Sci 32: 329'350. doi:10.1023/A:1013100717113.

- Gardner M (1990). Science ' Good, Bad and Bogus. Prometheus Books. ISBN 0879755733.

- Gardner M (1957). Fads and fallacies in the name of science. Dover Publications. ISBN 0486203948.

- Hansson SO (1996). "Defining pseudoscience". Philosophia naturalis 33: 169'176.

- Martin M (1994). "Pseudoscience, the paranormal, and science education". Science & Education 3: 1573'901. doi:10.1007/BF00488452. http://www.springerlink.com/content/g8u0371370878485/.

- Schadewald Robert J (2008). Worlds of Their Own - A Brief History of Misguided Ideas: Creationism, Flat-Earthism, Energy Scams, and the Velikovsky Affair. Xlibris. ISBN 978-1-4363-0435-1.

- Shermer M, Gould SJ (2002). Why People Believe Weird Things ' Pseudoscience, superstition, and other confusions of our time. New York: Holt Paperbacks. ISBN 0805070893.

- Wilson F (2000). The Logic and Methodology of Science and Pseudoscience. Canadian Scholars Press. ISBN 155130175X.

- Pratkanis, Anthony R. (July/August 1995). "How to Sell a Pseudoscience". Skeptical Inquirer 19 (4): 19'25. http://www.positiveatheism.org/writ/pratkanis.htm. Retrieved 2007-11-24.

[edit] References

- ^ "Pseudoscientific - pretending to be scientific, falsely represented as being scientific", from the Oxford American Dictionary, published by the Oxford English Dictionary; Hansson, Sven Ove (1996). 'Defining Pseudoscience', Philosophia Naturalis, 33: 169'176, as cited in "Science and Pseudo-science" (2008) in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. The Stanford article states: "Many writers on pseudoscience have emphasized that pseudoscience is non-science posing as science. The foremost modern classic on the subject (Gardner 1957) bears the title Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science. According to Brian Baigrie (1988, 438), '[w]hat is objectionable about these beliefs is that they masquerade as genuinely scientific ones.' These and many other authors assume that to be pseudoscientific, an activity or a teaching has to satisfy the following two criteria (Hansson 1996): (1) it is not scientific, and (2) its major proponents try to create the impression that it is scientific".

- For example, Hewitt et al. Conceptual Physical Science Addison Wesley; 3 edition (July 18, 2003) ISBN 0-321-05173-4, Bennett et al. The Cosmic Perspective 3e Addison Wesley; 3 edition (July 25, 2003) ISBN 0-8053-8738-2; See also, e.g., Gauch HG Jr. Scientific Method in Practice (2003).

- A 2006 National Science Foundation report on Science and engineering indicators quoted Michael Shermer's (1997) definition of pseudoscience: '"claims presented so that they appear [to be] scientific even though they lack supporting evidence and plausibility"(p. 33). In contrast, science is "a set of methods designed to describe and interpret observed and inferred phenomena, past or present, and aimed at building a testable body of knowledge open to rejection or confirmation"(p. 17)'.Shermer M. (1997). Why People Believe Weird Things: Pseudoscience, Superstition, and Other Confusions of Our Time. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. as cited by National Science Board. National Science Foundation, Division of Science Resources Statistics (2006). "Science and Technology: Public Attitudes and Understanding". Science and engineering indicators 2006. http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/seind06/c7/c7s2.htm.

- "A pretended or spurious science; a collection of related beliefs about the world mistakenly regarded as being based on scientific method or as having the status that scientific truths now have," from the Oxford English Dictionary, second edition 1989.

- ^ a b "Science and Pseudoscience" in. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Laudan, Larry (1983). 'The demise of the demarcation problem', in R.S. Cohan and L. Laudan (eds.), Physics, Philosophy, and Psychoanalysiss: Essays in Honor of Adolf Grünbaum, Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science , 76, Dordrecht: D. Reidel, pp. 111'127. ISBN 90-277-1533-5

- ^ Philosopher of science Paul Feyerabend wrote: "[T]he idea is detrimental to science, for it neglects the complex physical and historical conditions which influence scientific change. It makes our science less adaptable and more dogmatic." See Feyerabend, Paul. Outline of an anarchistic theory of knowledge, Marxists.org, accessed April 20, 2010.

- ^ The philosopher Karl Popper wrote that science often errs and that pseudoscience can stumble upon the truth, but what distinguishes them is the inductive method of the former, which proceeds from observation or experiment, and that its theories are falsifiable. See Popper, Karl. Conjectures and Refutations, Routledge and Keagan Paul, 1963, pp. 33'39.

- ^ Examples of college-level courses dealing with this topic are a course the University of Maryland entitled "Science & Pseudoscience" [1]; Pseudoscience, Scientism, and Science: A Short Course; The Teaching of Courses in the Science and Pseudoscience of Psychology: Useful Resources; HON 120 Natural Sciences and Society Spring 2006 Dr; What is science? What is pseudoscience?

- ^ Hurd, P. D. (1998). "Scientific literacy: New minds for a changing world". Science Education, 82, 407'416. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-237X(199806)82:3<407::AID-SCE6>3.0.CO;2-G See also Memorial Resolution: Paul DeHart Hurd, retrieved 8 April 2009.

- ^ "pseudoscience". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 2nd ed. 1989.

- ^ James Pettit Andrews, Robert Henry, History of Great Britain, from the death of Henry viii. to the accession of James vi. of Scotland to the crown of England 87

- ^ a b Magendie, F (1843) An Elementary Treatise on Human Physiology. 5th Ed. Tr. John Revere. New York: Harper, p 150. Magendie refers to phrenology as "a pseudo-science of the present day" (note the hyphen).

- ^ Bowler, Peter J. (2003). Evolution: The History of an Idea (3rd ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 0-52023693-9. p. 128

- ^ e.g. Gauch, Hugh G., Jr. (2003), Scientific Method in Practice, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-01708-4, [2] 435 pages, 3-5 ff

- ^ Gauch (2003), 191 ff, especially Chapter 6, "Probability", and Chapter 7, "inductive Logic and Statistics"

- ^ Popper, KR (1959) "The Logic of Scientific Discovery". The German version is currently in print by Mohr Siebeck (ISBN 3-16-148410-X), the English one by Routledge publishers (ISBN 0-415-27844-9).

- ^ Karl R. Popper: Science: Conjectures and Refutations. Conjectures and Refutations (1963), p. 43'86;

- ^ Paul R. Thagard "Why Astrology is a Pseudoscience" in PSA: Proceedings of the Biennial Meeting of the Philosophy of Science Association, Vol. 1978, Volume One: Contributed Papers (1978), pp. 223-234, The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Philosophy of Science Association 223 ff.

- ^ Bunge M (1983) "Demarcating science from pseudoscience" Fundamenta Scientiae 3:369-388

- ^ Feyerabend, P. (1975) Against Method: Outline of an Anarchistic Theory of Knowledge ISBN 0860916464 Table of contents and final chapter

- ^ For a perspective on Feyerabend from within the scientific community, see, e.g., Gauch (2003) at p.4: "Such critiques are unfamiliar to most scientists, although some may have heard a few distant shots from the so-called science wars."

- ^ Thagard PR (1978) "Why astrology is a pseudoscience" (1978) In PSA 1978, Volume 1, ed. Asquith PD and Hacking I (East Lansing: Philosophy of Science Association, 1978) 223 ff. Thagard writes, at 227, 228: "We can now propose the following principle of demarcation: A theory or discipline which purports to be scientific is pseudoscientific if and only if: it has been less progressive than alternative theories over a long period of time, and faces many unsolved problems; but the community of practitioners makes little attempt to develop the theory towards solutions of the problems, shows no concern for attempts to evaluate the theory in relation to others, and is selective in considering confirmations and non confirmations."

- ^ a b Cover JA, Curd M (Eds, 1998) Philosophy of Science: The Central Issues, 1-82

- ^ a b c d e f g h Popper, Karl (1963) Conjectures and Refutations.

- ^ a b Thagard PR (1978) "Why astrology is a pseudoscience" (1978)

- ^ Stephen Jay Gould, "Nonoverlapping magisteria", Natural History , March, 1997

- ^ [3] National Center for Science Education. Retrieved on 21-05-2010.

- ^ Royal Society statement on evolution, creationism and intelligent design http://www.royalsoc.ac.uk/news.asp?year=&id=4298

- ^ Popular Science Feature - When Science Fiction is Science Fact

- ^ Popper KR op. cit.

- ^ a b National Science Board (2006). "Chapter 7: Science and Technology: Public Attitudes and Understanding". Science and Engineering Indicators 2006. National Science Foundation. Belief in Pseudoscience (see Footnote 29). http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/seind06/c7/c7s2.htm#c7s2l3. Retrieved 3 March 2010.

- ^ Gallup Poll: Belief in paranormal phenomena: 1990, 2001, and 2005. Gallup Polls

- ^ e.g. Gauch (2003) op cit at 211 ff (Probability, "Common Blunders")

- ^ Paul Montgomery Churchland, Matter and Consciousness: A Contemporary Introduction to the Philosophy of Mind (1999) MIT Press. p.90. "Most terms in theoretical physics, for example, do not enjoy at least some distinct connections with observables, but not of the simple sort that would permit operational definitions in terms of these observables. [..] If a restriction in favor of operational definitions were to be followed, therefore, most of theoretical physics would have to be dismissed as meaningless pseudoscience!"

- ^ Gauch HG Jr. (2003) op cit 269 ff, "Parsimony and Efficiency"

- ^ Hines T (1988) Pseudoscience and the Paranormal: A Critical Examination of the Evidence Buffalo NY: Prometheus Books. ISBN 0879754192

- ^ Lakatos I (1970) "Falsification and the Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes." in Lakatos I, Musgrave A (eds) Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge pp 91-195; Popper KR (1959) The Logic of Scientific Discovery

- ^ e.g. Gauch (2003) op cit at 178 ff (Deductive Logic, "Fallacies"), and at 211 ff (Probability, "Common Blunders")

- ^ Macmilllan Encyclopedia of Philosophy Vol 3, "Fallacies" 174 ff, esp. section on "Ignoratio elenchi"

- ^ Macmillan Encyclopedia of Philosophy Vol 3, "Fallacies" 174 'ff esp. 177-178

- ^ Bunge M (1983) Demarcating science from pseudoscience Fundamenta Scientiae 3:369-388, 381

- ^ Thagard (1978)op cit at 227, 228

- ^ Lilienfeld SO (2004) Science and Pseudoscience in Clinical Psychology Guildford Press (2004) ISBN 1-59385-070-0

- ^ Ruscio J (2001) Clear thinking with psychology: Separating sense from nonsense, Pacific Grove, CA: Wadsworth

- ^ Peer review and the acceptance of new scientific ideas; Gitanjali B. Peer review -- process, perspectives and the path ahead. J Postgrad Med 2001, 47:210 PubMed; Lilienfeld (2004) op cit For an opposing perspective, e.g. Chapter 5 of Suppression Stories by Brian Martin (Wollongong: Fund for Intellectual Dissent, 1997), pp. 69-83.

- ^ Ruscio (2001) op cit.

- ^ a b Gauch (2003) op cit 124 ff"

- ^ Lakatos I (1970) "Falsification and the Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes." in Lakatos I, Musgrave A (eds.) Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge 91-195; Thagard (1978) op cit writes: "We can now propose the following principle of demarcation: A theory or discipline which purports to be scientific is pseudoscientific if and only if: it has been less progressive than alternative theories over a long period of time, and faces many unsolved problems; but the community of practitioners makes little attempt to develop the theory towards solutions of the problems, shows no concern for attempts to evaluate the theory in relation to others, and is selective in considering confirmations and disconfirmations."

- ^ Hines T, Pseudoscience and the Paranormal: A Critical Examination of the Evidence, Prometheus Books, Buffalo, NY, 1988. ISBN 0-87975-419-2. Thagard (1978) op cit 223 ff

- ^ Ruscio J (2001) op cit. p120

- ^ Devilly GJ (2005) Power therapies and possible threats to the science of psychology and psychiatry Australia and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 39:437-445(9)

- ^ e.g. archivefreedom.org which claims that "The list of suppressed scientists even includes Nobel Laureates!"

- ^ Devilly (2005) op cit. e.g. [4]

- ^ [5] National Science Board. 2006. Science and Engineering Indicators 2006 Two volumes. Arlington, VA: National Science Foundation (volume 1, NSB-06-01; NSB 06-01A)

- ^ National Science Board. "Science and Engineering Indicators 2006" (PDF). p. A7-14. http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/seind06/pdf/volume2.pdf. Retrieved 2009-05-03

- ^ FOX News (June 18, 2004). Poll: More Believe In God Than Heaven. Fox News Channel. http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,99945,00.html. Retrieved Apr. 26, 2009

- ^ Taylor, Humphrey (February 26, 2003). "Harris Poll: The Religious and Other Beliefs of Americans 2003". http://www.harrisinteractive.com/harris_poll/index.asp?pid=359. Retrieved Apr. 26, 2009

- ^ Justman, S. (2005). Fool's Paradise: The Unreal World of Pop Psychology. Ivan R. Dee. ISBN 1566636280

- ^ a b e.g. Drenth (2003) [6]; Herbert JD, et al. (2000) Science and pseudoscience in the development of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: implications for clinical psychology. Clin Psychol Rev. 20:945-71 [PMID 11098395])

- ^ Norcross J.C. Garofalo. A. Koocher.G.P. (2006) Discredited psychological treatments and tests: a Delphi poll. Professional Psychology. Research and Practice, 37: 515-522. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.37.5.515

- ^ (Devilly 2005:439)

- ^ a b Lindeman M (December 1998). "Motivation, cognition and pseudoscience". Scandinavian journal of psychology 39 (4): 257'65. doi:10.1111/1467-9450.00085. PMID 9883101. http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=0036-5564&date=1998&volume=39&issue=4&spage=257. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- ^ Gauch HG Jr (2003)op cit 3-7.

- ^ William F. Williams, editor (2000) Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience: From Alien Abductions to Zone Therapy Facts on File p. 58 ISBN 0-8160-3351-X

- ^ Hawking, Stephen W. (2000) The Nature of Time and Space, lectures delivered at the Isaac Newton Institute [7]: "Cosmology used to be considered a pseudo-science and the preserve of physicists who may have done useful work in their earlier years but who had gone mystic in their dotage. There are two reasons for this. The first was that there was an almost total absence of reliable observations. Indeed, until the 1920s about the only important cosmological observation was that the sky at night is dark. [However, in recent years] the range and quality of cosmological observations has improved enormously with the developments in technology."

- ^ Henry H. Bauer, "Scientific Literacy and the Myth of the Scientific Method", p 60

- ^ Radiation Hormesis

- ^ New On The Sepp Web

- ^ R. Hickey (1985). "Risks associated with exposure to radiation; science, pseudoscience, and opinion". Health Phys. 49 (5): 949'952. PMID 4066352.

- ^ M. Kauffman (2003). "Radiation Hormesis: Demonstrated, Deconstructed, Denied, Dismissed, and Some Implications for Public Policy". J. Scientific Exploration 17(3): 389'407.

- ^ Atwood KC (2004) Naturopathy, pseudoscience, and medicine: myths and fallacies vs truth. Medscape Gen Med6:e53

- ^ Laudan L (1996) "The demise of the demarcation problem" in Ruse, Michael, But Is It Science?: The Philosophical Question in the Creation/Evolution Controversy pp. 337-350.

- ^ McNally RJ (2003) Is the pseudoscience concept useful for clinical psychology? The Scientific Review of Mental Health Practice, vol. 2, no. 2 (Fall/Winter 2003)

- ^ Mendelian genetics was later rehabilitated, but not until after Vavilov died in the camps

- ^ as in debates concerning the relationship of race and intelligence. Imre Lakatos, Science and Pseudoscience (1973 Lecture Transcript)

[edit] External links

- Checklist for identifying dubious technical processes and products - Rainer Bunge, PhD

- Skeptic Dictionary: Pseudoscience - Robert Todd Carroll, PhD

- Distinguishing Science from Pseudoscience - Rory Coker, PhD

- Pseudoscience. What is it? How can I recognize it? - Stephen Lower

- Science and Pseudoscience - transcript and broadcast of talk by Imre Lakatos

- Science and Pseudo-Science: Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Science Needs to Combat Pseudoscience - A statement by 32 Russian scientists and philosophers

- Science, Pseudoscience, and Irrationalism - Steven Dutch

- Skeptic Dictionary: Pseudoscientific topics and discussion - Robert Todd Carroll

- Why Is Pseudoscience Dangerous? - Edward Kruglyakov

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

SOURCES.COM is an online portal and directory for journalists, news media, researchers and anyone seeking experts, spokespersons, and reliable information resources. Use SOURCES.COM to find experts, media contacts, news releases, background information, scientists, officials, speakers, newsmakers, spokespeople, talk show guests, story ideas, research studies, databases, universities, associations and NGOs, businesses, government spokespeople. Indexing and search applications by Ulli Diemer and Chris DeFreitas.

For information about being included in SOURCES as a expert or spokesperson see the FAQ . For partnerships, content and applications, and domain name opportunities contact us.