| Home | Sources Directory | News Releases | Calendar | Articles | | Contact | |

Red Summer of 1919

Red Summer describes the bloody race riots that occurred in the United States during the summer and early autumn of 1919. In most instances, whites attacked African Americans in more than two dozen American cities, though in some cases blacks responded in groups to a single action against one of their number, notably in Chicago, which, along with Washington, D.C. and Elaine, Arkansas, witnessed the greatest number of fatalities.[1]

Contents |

[edit] Name

James Weldon Johnson coined the term "Red Summer." Employed since 1916 by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) as a field secretary, he built and revived local chapters of that organization. In 1919, he organized protest against the racial violence of 1919.[2][3]

[edit] Context

On April 11, 1919, the US delegate rejected Racial Equality Proposal in the Paris Peace Conference, then the violent reaction occurred by African Americans.[4]

With the manpower mobilization and military draft of World War I and immigration from Europe cut off, the industrial cities of the North and Midwest experienced severe labor shortages. Northern manufacturers recruited throughout the South and an exodus ensued.[5] By 1919, it was estimated that 500,000 African Americans had emigrated from the South to the industrial cities of the North and Midwest during World War I.[1] African-American workers filled new positions as well as many jobs formerly held by whites. In some cities, they were hired as strikebreakers, especially during strikes of 1917.[5] This increased resentment and suspicion among whites, especially the working class. Following the war, rapid demobilization and the removal of price controls led to inflation and unemployment that increased competition for jobs.

During the Red Scare of 1919-20 following the Russian Revolution, anti-Bolshevik sentiment quickly replaced the anti-German sentiment of the World War I years. Many politicians and government officials, along with a large part of the press and the public, feared an imminent attempt to overthrow the government of the United States and the creation of a new regime modeled on that of the Soviets. In that atmosphere of public hysteria, radical views as well as moderate dissents were often characterized as un-American or subversive, including the advocacy of racial equality, of labor rights, or even the rights of victims of mob violence to defend themselves. Close ties between recent European immigrants and radical political ideas and organizations fed those anxieties as well.

[edit] Events

In the autumn of 1919, Dr. George E. Haynes, an educator employed as Director of Negro Economics at the U.S. Department of Labor, produced a report on that year's racial violence designed to serve as the basis for an investigation by the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary. It cataloged 26 separate riots on the part of whites attacking blacks in widely scattered communities.[1]

In addition, he reported that at least 43 African Americans were lynched, while another eight men were burned at the stake between January 1 and September 14, 1919.[1]

Unlike earlier race riots in U.S. history, the 1919 riots were among the first in which blacks resisted white attacks. A. Philip Randolph defended the right of blacks to commit violence in self-defense.[2]

Martial law was imposed in Charleston, South Carolina,[1] where men of the U.S. Navy led the race riot of May 10, in which Isaac Doctor, William Brown, and James Talbot, all black men, were killed. Five white men and eighteen black men were injured in the riot. A Naval investigation found that four U.S. sailors and one civilian'all white men'were responsible for the outbreak of violence.[6]

The race riot in Longview, Texas early in July led to the deaths of at least four men and the destruction of the African-American housing district in the town.[1]

On July 3, The 10th U.S. Cavalry, a segregated African-American unit founded in 1866, was attacked by local police in Bisbee, Arizona.[7]

In Washington, D.C., white men, many in military uniforms, responded to the rumored arrest of a black man for rape with 4 days of mob violence, rioting and beatings of random black people on the street. When police refused to intervene, the black population fought back. Troops tried to restore order as the city closed saloons and theaters to discourage assemblies. A summer rainstorm had more of an effect. When the violence ended, 10 whites were dead, including 2 police officers, and 5 blacks. Some 150 people had been the victims of attacks.[8]

The NAACP sent a telegram to President Wilson to point out:[9]

- ...the shame put upon the country by the mobs, including United States soldiers, sailors, and marines, which have assaulted innocent and unoffending negroes in the national capital. Men in uniform have attacked negroes on the streets and pulled them from streetcars to beat them. Crowds are reported ...to have directed attacks against any passing negro....The effect of such riots in the national capital upon race antagonism will be to increase bitterness and danger of outbreaks elsewhere. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People calls upon you as President and Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces of the nation to make statement condemning mob violence and to enforce such military law as situation demands.

"The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People respectfully enquires how long the Federal Government under your administration intends to tolerate anarchy in the United States?"

August 29, 1919

In Norfolk, Virginia, a white mob attacked during the homecoming celebration for African-American soldiers. At least six people were shot, and local police called in Marines and Navy personnel to restore order.[1]

The summer's greatest violence occurred during rioting in Chicago starting on July 27. Chicago's beaches along Lake Michigan were segregated in practice, if not by law. A black youth who swam into the area customarily reserved for whites was stoned and drowned. Blacks responded violently when the police refused to take action. Violence between mobs and gangs lasted 13 days. The resulting 38 fatalities included 23 blacks and 15 whites. Injuries numbered 537 injured, and 1,000 black families were left homeless.[10] Some 50 people were reported dead. Unofficial numbers were much higher. Hundreds of mostly black homes and businesses on the South Side were destroyed by mobs, and a militia force of several thousand was called in to restore order.[1]

At the end of July the Northeastern Federation of Colored Women's Clubs, from their Providence, Rhode Island convention, denounced the rioting and burning of negroes' homes then happening in Chicago and asked Wilson "to use every means within your power to stop the rioting in Chicago and the propaganda used to incite such."[11] At the end of August the NAACP protested again, noting the attack on the organization's secretary in Austin, Texas the previous week. Their telegram said: "The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People respectfully enquires how long the Federal Government under your administration intends to tolerate anarchy in the United States?" [12]

During the Knoxville, Tennessee race riot at the end of August, a mob stormed the county jail to release 16 white prisoners, including convicted murderers. Turning to the African-American business district, the mob killed at least seven and wounded more than 20 people.[13][14]

At the end of September, the race riot in Omaha, Nebraska witnessed violence on the part of a white mob of more than 10,000 who burned the county courthouse and destroyed property valued at more than a million dollars. One man, Will Brown, was lynched. Troops under the command of Major General Leonard Wood, friend of Theodore Roosevelt and a leading candidate for the Republican nomination for President in 1920, restored order.[15]

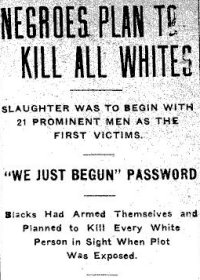

The Elaine, Arkansas race riot was different in that it occurred in the rural South. It began when a white man, intent on arresting a black bootlegger, was shot by black sharecroppers who had been warned of possible trouble, and were defending a meeting of the local chapter of the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America. White landowners then formed a group to attack the African-American farmers. Five whites and between 100 and 200 blacks died as a result. Arkansas Governor Charles Hillman Brough appointed a Committee of Seven, prominent local white businessmen, to investigate. It concluded that the sharecroppers' Union, a Socialist enterprise, was "established for the purpose of banding negroes together for the killing of white people." That story made headlines like this in the Dallas Morning News: "Negroes Seized in Arkansas Riots Confess to Widespread Plot; Planned Massacre of Whites Today." Several agents of the Justice Department's Bureau of Investigation spent a week interviewing those involved'though they spoke to none of the sharecroppers'and reviewing documents. They filed a total of 9 reports making it clear that there was no evidence of a conspiracy on the part of the sharecroppers to murder anyone. Their superiors at Justice ignored their analysis. Seventy-nine blacks were later tried and convicted, with 12 sentenced to death. The remainder accepted prison terms of up to 21 years. Appeals of their cases went to the U.S. Supreme Court which reversed the verdicts because of trial errors. Federal oversight of defendants' rights was increased.[16]

[edit] Chronology

Based on Haynes' report as summarized in the New York Times except as noted.[1]

[edit] Responses

"We appeal to you to have your country undertake for its racial minority that which you forced Poland and Austria to undertake for their racial minorities."

November 25, 1919

Protests and appeals continued for weeks. A letter in late November from the National Equal Rights League used Wilson's international advocacy for human rights against him: "We appeal to you to have your country undertake for its racial minority that which you forced Poland and Austria to undertake for their racial minorities."[18]

In September 1919, in response to the Red Summer, the African Blood Brotherhood formed to serve as an "armed resistance" movement.

[edit] Haynes report

The Haynes report of October 1919[1] was a call for national action. Haynes said that states had shown themselves "unable or unwilling" to put a stop to lynchings. The fact that white men had been lynched in the North as well, he argued, demonstrated the national nature of the overall problem: "It is idle to suppose that murder can be confined to one section of the country or to one race." He then connected lynchings to riots:

- Persistence of unpunished lynchings of negroes fosters lawlessness among white men imbued with the mob spirit, and creates a spirit of bitterness among negroes. In such a state of public mind a trivial incident can precipitate a riot.

- Disregard of law and legal process will inevitably lead to more and more frequent clashes and bloody encounters between white men and negroes and a condition of potential race war in many cities of the United States.

- Unchecked mob violence creates hatred and intolerance, making impossible free and dispassionate discussion not only of race problems, but questions on which races and sections differ.

[edit] Press coverage

In mid-summer, in the middle of the Chicago riots, a "federal official" told the New York Times that the violence resulted from "an agitation, which involves the I.W.W., Bolshevism and the worst features of other extreme radical movements." He supported that claim with copies of negro publications that called for alliances with leftist groups, praised the Soviet regime, and contrasted the courage of jailed Socialist Eugene V. Debs with the "school boy rhetoric" of traditional black leaders. The Times characterized the publications as "vicious and apparently well financed," mentioned "certain factions of the radical Socialist elements," and reported it all under the headline: "Reds Try to Stir Negroes to Revolt."[19]

In response, black leaders like Bishop Charles Henry Phillips of the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church asked blacks to shun violence in favor of "patience" and "moral suasion." Though stating his opposition to any propaganda favoring violence he also said: "I cannot believe that the negro was influenced by Bolshevist agents in the part he took in the rioting. It is not like him to be a traitor or a revolutionist who would destroy the Government. But then the reign of mob law to which he has so long lived in terror and the injustices to which he has had to submit have made him sensitive and impatient."[20]

In presenting the Haynes report in early October, The New York Times provided a context his report did not mention. Haynes documented violence and inaction on the state level. The Times saw "bloodshed on a scale amounting to local insurrection" as evidence of "a new negro problem" because of "influences that are now working to drive a wedge of bitterness and hatred between the two races." Until recently, the Times said, black leaders showed "a sense of appreciation" for what whites had suffered on their behalf in fighting a civil war that "bestowed on the black man opportunities far in advance of those he had in any other part of the white man's world." Now militants were supplanting Booker T. Washington, who had "steadily argued conciliatory methods." The Times continued:[1]

- Every week the militant leaders gain more headway. They may be divided into general classes. One consists of radicals and revolutionaries. They are spreading Bolshevist propaganda. It is reported that they are winning many recruits among the colored race. When the ignorance that exists among negroes in many sections of the country is taken into consideration the danger of inflaming them by revolutionary doctrine may [be] apprehended.... The other class of militant leaders confine their agitation to a fight against all forms of color discrimination. They are for a program on uncompromising protest, 'to fight and continue to fight for citizenship rights and full democratic privileges.'

As evidence of militancy and Bolshevism, the Times named W.E.B. Du Bois and quoted his editorial in the publication he edited, The Crisis: "Today we raise the terrible weapon of self-defense....When the armed lynchers gather, we too must gather armed." When the Times endorsed Haynes' call for a bi-racial conference to establish "some plan to guarantee greater protection, justice, and opportunity to negroes that will gain the support of law-abiding citizens of both races," it endorsed discussion with "those negro leaders who are opposed to militant methods." The only "militant method" it cited was a call for self defense.

In mid-October government sources again provided the Times with evidence of Bolshevist propaganda targeting America's black communities. This account did not blame Red agitation for recent racial violence, but set Red propaganda in the black community into a broader context, since it was "paralleling the agitation that is being carried on in industrial centres of the North and West, where there are many alien laborers." Vehicles for this propaganda about the "doctrines of Lenin and Trotzky" included newspapers, magazines, and "so-called 'negro betterment' organizations." Quotations from such publications contrasted the recent violence in Chicago and Washington, D.C. with "Soviet Russia, a country in which dozens of racial and lingual types have settled their many differences and found a common meeting ground, a country which no longer oppresses colonies, a country from which the lynch rope is banished and in which racial tolerance and peace now exist." The Times cited one publication's call for unionization: "Negroes must form cotton workers' unions. Southern white capitalists know that the negroes can bring the white bourbon South to its knees. So go to it."[21]

Coverage of the root causes of the events in Elaine, Arkansas evolved as the violence stretched over several days. A dispatch from Helena, Arkansas to the New York Times datelined October 1 said: "Returning members of the [white] posse brought numerous stories and rumors, through all of which ran the belief that the rioting was due to propaganda distributed among the negroes by white men."[22] The next day's report added detail: "Additional evidence has been obtained of the activities of propagandists among the negroes, and it is thought that a plot existed for a general uprising against the whites." A white man had been arrested and was "alleged to have been preaching social equality among the negroes." Part of the headline was: "Trouble Traced to Socialist Agitators."[23] A few days later a Western Newspaper Union dispatch captioned a photo using the words "Captive Negro Insurrectionists."[24]

[edit] Government activity

J. Edgar Hoover, then at the very start of his career in government, provided an analysis of the riots to the Attorney General. He blamed the July Washington, D.C. riots on "numerous assaults committed by Negroes upon white women." For the October events in Arkansas, he blamed "certain local agitation in a Negro lodge." A more general cause he cited was "propaganda of a radical nature." He charged that socialists were feeding propaganda to black-owned magazines like The Messenger, that in turn aroused their black readers. The white perpetrators of violence went unmentioned. As chief of the Radical Division within the U.S. Department of Justice, Hoover began an investigation of "negro activities" and particularly targeted Marcus Garvey because he thought his newspaper Negro World preached Bolshevism.[8]

[edit] See also

[edit] References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k New York Times: "For Action on Race Riot Peril," October 5, 1919, accessed January 20, 2010. This newspaper article includes several paragraphs of editorial analysis followed by Dr. Haynes' report, "summarized at several points."

- ^ a b Alana J. Erickson, "Red Summer" in Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History (NY: Macmillan, 1960), 2293-4

- ^ George P. Cunningham, "James Weldon Johnson," in Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History (NY: Macmillan, 1960), 1459-61

- ^ Paul Gordon Lauren (1988), Power And Prejudice: The Politics And Diplomacy Of Racial Discrimination Westview Press ISBN 0813306787 p.99

- ^ a b David M. Kennedy, Over Here: The First World War and American Society (NY: Oxford University Press, 2004), 279, 281-2

- ^ Walter C. Rucker, James N. Upton. Encyclopedia of American Race Riots. Volume 1. 2007, page 92-3

- ^ Rucker, Walter C. and Upton, James N. Encyclopedia of American Race Riots (2007), 554

- ^ a b Kenneth D. Ackerman, Young J. Edgar: Hoover, the Red Scare, and the Assault on Civil Liberties (NY: Carroll & Graf, 2007), 60-2

- ^ New York Times: "Protest Sent to Wilson," July 22, 1919. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica: "Chicago Race Riot of 1919". Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ New York Times: "Negroes Appeal to Wilson,"" August 1, 1919. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- ^ New York Times: Negro Protest to Wilson," August 30, 1919. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- ^ Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture: Knoxville Riot of 1919. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- ^ Robert Whitaker, On the Laps of Gods: The Red Summer of 1919 and the Struggle for Justice that Remade a Nation (NY: Random House, 2008), 53

- ^ David, Pietrusza, 1920: The Year of Six Presidents (NY: Carroll & Graf, 2007), 167-72

- ^ Robert Whitaker, On the Laps of Gods: The Red Summer of 1919 and the Struggle for Justice that Remade a Nation (NY: Random House, 2008), 131-42. Whittaker's work is a detailed account of the Arkansas events, not a general study of the Red Summer.

- ^ Robert Whitaker, On the Laps of Gods: The Red Summer of 1919 and the Struggle for Justice that Remade a Nation (NY: Random House, 2008), 51

- ^ New York Times: "Ask Wilson to Aid Negroes," November 26, 1919. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- ^ New York Times: "Reds Try to Stir Negroes to Revolt," July 28, 1919. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- ^ "Denies Negroes are 'Reds'" New York Times August 3, 1919, accessed January 28, 2010. Phillips was based in Nashville, Tennessee.

- ^ New York Times: "Reds are Working among Negroes," October 19, 1919. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- ^ New York Times: "None Killed in Fight with Arkansas Posse," October 2, 1919. Retrieved January 27, 2010.

- ^ New York Times: "Six More are Killed in Arkansas Riots," October 3, 1919. Retrieved January 27, 2010.

- ^ New York Times: "[untitled]" October 12, 1919. Retrieved January 27, 2010.

[edit] Further reading

- Dray, Philip. At the Hands of Persons Unknown: The Lynching of Black America, New York: Random House, 2002

- Tuttle, William M., Jr. Race Riot: Chicago in the Red Summer of 1919. 1970. Blacks in the New World. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1996

|

SOURCES.COM is an online portal and directory for journalists, news media, researchers and anyone seeking experts, spokespersons, and reliable information resources. Use SOURCES.COM to find experts, media contacts, news releases, background information, scientists, officials, speakers, newsmakers, spokespeople, talk show guests, story ideas, research studies, databases, universities, associations and NGOs, businesses, government spokespeople. Indexing and search applications by Ulli Diemer and Chris DeFreitas.

For information about being included in SOURCES as a expert or spokesperson see the FAQ or use the online membership form. Check here for information about becoming an affiliate. For partnerships, content and applications, and domain name opportunities contact us.